Incomparables

A review of

Nouvelles

impressions de Raymond Roussel

(New

Impressions of Raymond Roussel)

Place: Palais de Tokyo

13, avenue

du Prˇsident Wilson, 75 116 Paris

Level

1 - Galerie Seine

Dates: 27/02/2013 - 20/05/2013

published 3/11/2013

@

http://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/incomparables/

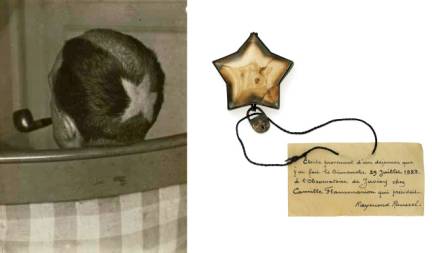

Marcel

Duchamp by Man Ray (1920) & Etoile cosmique (1923) by

Raymond Roussel

Ē My

soul is a strange factory Č

-Raymond

Roussel

New Impressions of Raymond Roussel points us towards an intellectual

history that maps out artÕs role in creating a social allegory for the poetic

psychoanalysis[1] of

mechanized pleasure - in circular struggle with the mechanized mass killings of

World War I and II, the holocaust, and Hiroshima. And the rewards of such

exhausting circularity are considerable, given both the historical significance

of Raymond RousselÕs influence and its unapologetic relevance to todayÕs cyber

culture - with its intransigent obliqueness and mechanical dizziness.

But if I were going to generate an art

exhibition as homage to a particularly flamboyant artist,[2]

even if un peu obscur,

I would think that it would be advantageous to try to match the aesthetic

qualities of that person (absurdly intricate mechanical interlacings) with the

showÕs general aesthetic. Unfortunately, that was not the least bit achieved

with the homage to the wildly creative dandy writer Raymond Roussel (1877-1933)[3]

that is at the Palais de Tokyo centre d'art contemporain in Paris.

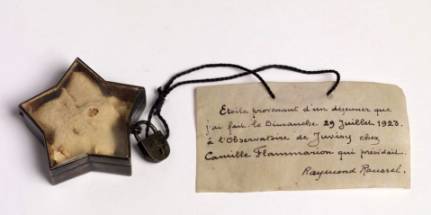

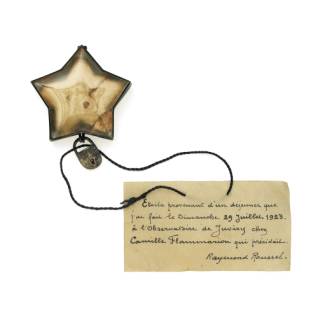

While access to much of the remarkable

work here (including five of RousselÕs otherworldy hand written manuscript

pages for his last book Comment j'ai ˇcrit certains de mes livres (How I Wrote Certain of my Books) and a

wonderful cookie-encasing sculpture memento called Etoile cosmique (Cosmic Star) - a glass and silver case

that Roussel had made for a star-shaped biscuit he brought back from lunch in

Juvisy-sur-Orge with the astronomer Camille Flammarion (1842-1925) on July 29,

1923) is to be appreciated and relished, the cavernous half-finished Level 1

Galerie Seine devoured

and neutralized any stylistic moods of gamesmanship that are associated with

Roussel: such as the famously extravagant, yet intricately hermetic, elaborate

mechanamorphic constructions that verged on the exuberantly preposterousness of

a machine running infinitely wild.

Perhaps if I had seen the other two

manifestations of this show - Impressions of Raymond Roussel held at the Museo Reina Sofia (Madrid)

in 2011 and the Museu Serralves (Porto) in 2012 - I may not have felt so

disappointed in the general lack of neurotic deliriousness experienced in this

one.

Granted that Raymond RousselÕs disregard

for financial restraint[4]

cannot be matched by the Palais de Tokyo, but still the gutted construction

materials hanging overhead in this ugly cavernous space takes the eye and mind

out of the magnificently intricate labyrinthine quality typical of his

extravagant writings: as established in the prose work Impressions dÕAfrique (1910) (a work that features a painting

machine that duplicates the color spectrum of the sky at dawn),[5]

Locus Solus (1914)

(like Impressions dÕAfrique, written according to formal constraints based on homonymic puns) and the obsessive but convulsingly

poetic Nouvelle Impressions dÕAfrique (1932).[6]

Thus the larger the art (even as it was needed to fill this mammoth half-raw

space) the worse it connected to RousselÕs sense of virtual impenetrability

through mechanical precision.

Mike Kelly, Kandors

10B (Exploded Fortress of Solitude) (2011)

Mike Kelly, Kandors

10B (Exploded Fortress of Solitude) (2011)

Rodney Graham, Camera

Obscura Mobile (1995-1996)

Mike KellyÕs

lumbering black cave Kandors 10B (Exploded Fortress of Solitude) (2011) and

Rodney GrahamÕs Camera Obscura Mobile (1995-1996) installation were

particularly unmatched to RousselÕs obsessive minute attention; a concentration

that is capable of whirling together copious narratives from a veiled network

of murky puns and obscured double entendres in a way that anticipates Oulipian.

Mark MandersÕs steamy black connectivist sculpture Mind Study (2011),

Giuseppe GabelloneÕs beautiful silver sculpture LÕAssetalo (Thirsty

Man) (2008) and Jacques CarelmanÕs droll motion sculpture Le Diamont (The

Dimond) (1975) worked only a bit better in reinforcing a spirit of intricate

mechanicalness as they each ate up almost an entire room. A relatively

fascinating installation by Andrˇ Maranha, Pedro Morais, Jorge Queiroz and

Francisco Tropa called Tres Moscas (Three Flies) (2012) did eat an

entire room and only delivered limited thematic power in terms of absurd

interlacing.

Andrˇ

Maranha, Pedro Morais, Jorge Queiroz and Francisco Tropa, Tres Moscas (Three

Flies) (2012)

Giuseppe

Gabellone, LÕAssetalo, (Thirsty Man) (2008)

Mark

Manders, Mind Study (2011)

Mark

Manders, Mind Study & Jean Tinguely, Requiem pour une

feuille morte (Requiem for a Dead Leaf) (1966-67) (on the wall)

Much more

capable of such finicky and arcane mesmerizing rhythms was the more intimate

yet preposterous work of Thomas Bayrle (his deadpan pulsating romantic machine Spatz

von Paris (2011) is one of the highlights of the show). Rodney GrahamÕs

series of books called The System worked well in the context and it

was captivating to see displays of the literary journal Revue Locus Solus,

established by American writers John Ashbery, Harry Mathews, Kenneth Koch and

James Shuyler. Published in Paris between 1961 and 1962, the journal formed a

bridge between French authors, both historical and contemporary, and writers

from the New York School and the Beat Generation. The

Coll¸ge de Pataphysique was represented by the writer Jean Ferry who published

several studies devoted to Roussel, including LÕAfrique des Impressions, a detailed

analysis which consists of considering the text as instructions for users and

reconstructing, in the form of maps, diagrams and schedules, the journeys and

events that took place at Ponukˇlˇ, an imaginary place in RousselÕs Africa. Two

comical cosmic Joseph Cornell boxes, Blue Sand Box and Sand

Fountain from the early 1950s pleased me, as they bracketed a stream of

photographed drawings of fantastic imaginary architecture from 1857 by

Victorien Sardou - as did an early Pataphysical video by Jean-Christophe

Averty.

The

irascible Salvador Dal’ is represented with his short motion picture Impressions

de la Haute Mongolie (1975), made with the filmmaker Josˇ Montes-Baquer. Dal’ read

RousselÕs books as early as the 1920s and Roussel had a great influence on

Dal’Õs Ņcritical paranoiaÓ method. Dal’, who died with a copy of Impressions

d'Afrique on his bedside table, believed him to be one of France's greatest

writers ever. Jean Tinguely is inserted, rightly, into this mix with a

brain-teasing manic lithograph from 1966-67 called Requiem pour une feuille

morte (Requiem for a Dead Leaf), rather than an expected endless

drawing machine contraption, that would have more directly interlocked with

RousselÕs imagined painting machine.

And

RousselÕs major inspiration (along with novelist and naval officer Pierre

Loti), the author Jules Verne, has a wacky lithograph of a flat globe studded

with images entitled Around the World in Eighty Days from 1880.

Roussel greatly admired the works of Verne - which he read over and over again,

fascinated with their extraodinary voyages and machines, full of bachelor

scientists completely absorbed in positivist exploratory dreams taken to

delirious extremes. At that scale of interlacing, some of the hypnotic effect

of RousselÕs capacious playful circularity is possible to feel.

However, Gabriele Di MatteoÕs

contribution to the showÕs circularity is essential. His hand-painted over

digital-painting Marcel Duchamp, a life in pictures by Andrˇ Raffray illustrates

the time when Duchamp attended a showing of Impressions dÕAfrique in 1912, an

experience Duchamp would describe as revelatory. As Gabriele Di Matteo

depicts, Duchamp, along with Guillaume Appollinaire, Picabia and PicabiaÕs wife

Gabrielle Buffet, attended a performance of Impressions of Africa: the play

by Roussel based on his book. Duchamp later credited Roussel with the

inspiration for his The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The

Large Glass). There are several original notes by Duchamp and a drawing that he

made for The Large Glass in 1912-1915 in the show, as well as

quite a few photos of Duchamp with The Large Glass. Among them

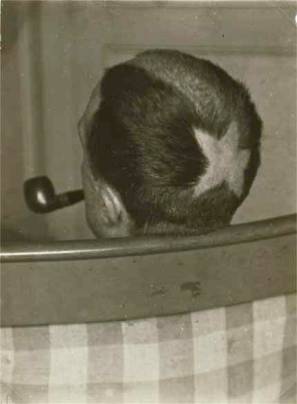

is the striking photo of Duchamp that was taken by Man Ray in 1920 that shows a

star carved out in DuchampÕs hair. This work connects ludicrously well with

RousselÕs star shaped cookie piece, Etoile cosmique, from just

three years later.

Man Ray,

photo of Marcel Duchamp (1920) La Tonsure

Raymond

Roussel, Etoile cosmique (1923)

Collection

littˇraire Pierre Leroy

Historically,

the mechanamorphic impulse behind Marcel Duchamp's works from 1912 (that

derived a good deal from Roussel) is of great significance. That is when

Duchamp started producing paintings and drawings depicting mechanized sex acts

such as Mechanics of Modesty and The Passage from the Virgin

to the Bride - and the fantastic machine-body work The Bride Stripped Bare

by Her Bachelors, Even that follow his exposure to the play Impressions

dÕAfrique - is an inescapable point of reference for the avant-garde of the

20th century. The same may be said for Francis Picabia (who has a room of

paintings all to himself at the show La Collection Michael Werner just a

stone throw away at the Musˇe d'Art Moderne Ville de Paris).

The elaborateness of the machine, for

Duchamp and Picabia, became the symbol of sexual bliss[7]

attainable through concept connected to auto-sexual autonomy in contradiction

to the horror that mechanized war had brought. By hypnotizing attention, the

machine freed them from troubling obsessions and personal hang-ups through the

alternative model of android life; intimating both our rush of desperation and

our ecstatic release, refracted through a web of glazed impersonality. If the

machine, as a representative of order, was a fascination Duchamp and Picabia

used to balance out the ageÕs clumsiness, whether of the mind or flesh,

RousselÕs mechanamorphic production and machine forms refigured the human body

into an almost mechanized substance.

In The Bride Stripped Bare by the

Bachelors, Even, which

positions a central bride machine over a bachelor apparatus, Duchamp, with the

strictness of machinery, applies fantasy to seduction and masturbation. In a

way, Duchamp suggests that we (as viewers) can use his art as a vehicle for

self-transcendence into a kind of dream world of nonsense sex. This rabbit-hole

logic he took from Roussel.

So New

Impressions of Raymond Roussel succeeds when it outlines an

eccentric expanding circular history of 20th-century art, linking the points

between artists and writers who have talked of the influence of this author and

his writings on their work: starting with Dada (Duchamp, Man Ray, Picabia),

then Andrˇ Breton and the Surrealists (like Michel Leiris, Salvador Dal’, Jean

Cocteau) to Neo-Dada Nouveau rˇalisme (Jean Tinguely) through Oulipo (Georges

Perec) Pataphysicians (Jean Ferry, Jean-Christophe Averty and the Coll¸ge de

Pataphysique) and the authors of the nouveau roman (like Alain Robbe-Grillet).

As noted above, his most direct influence in the English-speaking world was

on the New York School of poets John Ashbery, Harry Mathews, James Schuyler, and Kenneth Koch.

Writing as

art Š or - art as writing: this is the theoretical ripe fruit plucked from Nouvelles

impressions de Raymond Roussel - art theory as art - made

conceivable by RousselÕs inventions of language machines that produced texts

through the use of repetitions and combination/permutations. This machine-like

logic provides art with a seemingly pure spectacle of endless variety of

textual games and combinations flowing in circular form. (We see and feel this

most fully, however, in the sprawling and dazzling Julio Le Parc kinetic op art

retrospective on the first floor of the Palais de Tokyo, rather than in this

show.)

And there

are lessons here for painting, also. Within this writing process Roussel

described a number of fantastic machines, including a painting machine in his

novel Impressions of Africa. This painting machine wonderfully

describes and foresees the arrival of computer-robotic technology and it's

application to visual art which we have available to us today, a century after

he envisioned it.

The web also

regenerates deep connections to the past; so cyberspace, this territory which

stretches out from hypertext to the world-wide computer network, from virtual

reality to video games, might also be theorized as the domain of RousselÕs idea

of reduplicating without duplication, reiterating without repeating: his game-of-mirrors

cosmos. His is a strident activity lost in an infinite navigation from one sort

of encounter to another in which the affirmation of the other keeps appearing

and disappearing in the play of mechanical maneuvers (or mechanisms) destined

to avert gratification. This is where the bachelor apparatus of Duchamp repeats

itself ad infinitum by transmitting the machine via an alter-ego.

But too, New

Impressions of Raymond Roussel reminds us that Raymond Roussel's

themes and procedures also involved imprisonment and liberation, exoticism,

cryptograms and torture by language - all formally reflected in his working

technique with its inextricable play of double images, repetitions, and

impediments, all giving the impression of the pen running on by itself through

the dreamy usage and baroque play of mirrored form.

Roussel's

running on repetition technique, as used in the Thomas Bayrle sculpture, for

example, lends itself well to the creation of unforeseen, automatic and

spontaneously art which gives me the feeling of prolonging action into eternity

through the ceaseless, fantastic constructions of the work itself, transmitting

an altered, exalted and orgasmic state of mind which after the initial dazzling

creates one predominant overall effect: that of creating doubt through

mechanical discourse.

The image of

enclosure is common with Roussel where a secret to a secret is held back,

systematically imposing a formless anxiety in the reader through the

labyrinthine extensions and doublings, disguises and duplications of his texts,

which make all speech and vision undergo a moment of annihilation.

New

Impressions of Raymond Roussel succeeds when it presents to us

through intimacy the model of quiet perfection of the eternally repetitive

mechanical machine which functions independently of time and space, pulling us

into a logic of the infinite. We can learn this from Roussel's final rebus-like

book, Comment j'ai ˇcrit certains de mes livres (How I

Wrote Certain of my Books); the last of his conceptual machines, the machine

which contains and repeats within its mechanism all those mental machines he

had formerly described and put into motion, making evident the machine which

produced all of his machines - the master machine.[8]

All of these machines map out an eccentric spiral space that is circular in

nature and thus an abstract attempt at eliminating time. They reproduce the old

myths of departure, of loss and of return. They construct a crisscrossed

mechanical map of the two great mythic spaces so often explored by western

imagination: space that is rigid and forbidden, containing the quest, the

return and the treasure (for example the geography of the Argonauts and the

labyrinth) - and the other space of polymorphosis noise: the visible

transformation of instantly crossed frontiers and borders, of strange

affiliations, of spells, and of symbolic replacements (the space of the

Minotaur).

Nouvelles

impressions de Raymond Roussel potentially removes us out of our

quiet and glib indolence and points us in the potent direction of expanding

intensity. I believe that shows like Nouvelles impressions de Raymond

Roussel are critical to us now because the counter-mannerist excess found

there can problematize the popular simulacra that art has become - and make

livelier the underground intricately strange privateness of the human animal.

***

Joseph Nechvatal

***

Nouvelles

impressions de Raymond Roussel (New Impressions of Raymond Roussel) has

work in it by: Mathieu K. Abonnenc, Jean-Michel Alberola, Jean-Christophe

Averty, Zbynek Baladr‡n, Thomas Bayrle, Jacques

Carelman, Guy de Cointet, Coll¸ge de Pataphysique, Joseph

Cornell, Salvador Dal’, Gabriele Di Matteo, Thea Djordjadze, Marcel

Duchamp, Giuseppe Gabellone, Rodney Graham, Jo‹o Maria Gusm‹o

& Pedro Paiva, Mike Kelley, Revue Locus Solus, Pierre

Loti, Sabine Macher, Man Ray, Mark Manders, Andrˇ Maranha,

Pedro Morais, Jorge Queiroz et Francisco Tropa, Jean-Michel

Othoniel, Victorien Sardou, Joe Scanlan, Jean

Tinguely, Jules Verne.

Raymond

Roussel, Etoile cosmique (1923)