Groebel's Ghosts

What do

the following men have in common: Baron Rowton (1838-1903), philanthropist

and private secretary to Benjamin Disraeli, the revolutionary and later dictator

Josef Stalin (1878-1953) and the writers Jack London (1876-1910) and George

Orwell (1903-1950)? Hardly coevals in the strictest sense - an encounter

between them would have been more than improbable, and even if the

self-avowed socialist Orwell condemned "real socialism" of the

Stalinist mould in his novels, there is no record that any of these

protagonists knew of each other's respective spheres of activity.

Nevertheless, their lives do intersect at one point, if one were to imagine a

possible rendezvous in a certain "Tower House" in London's

impoverished east end. Founded by Baron Rowton as a new type of "working

men's hostel" or doss house for homeless workers, Jack London, Stalin

and Orwell, amongst others, each spent a night there. Whereas Stalin,

attending the 5th Congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Workers Party in

1907, omits the fact of his stay from his memoirs, London and Orwell process

their experiences via literature and journalism; the former in his undercover

reportage The People of the Abyss (1903) about London slums, the latter in

Down and out in Paris and London, published in 1933.

Safe from

Demons is the title of Matthias Groebel's latest project, in which he brings

together the various branches of these diverse individuals' lives. And yet

the present hardly seems to be safe from demons, inasmuch as the shadows of

the past - as reported in recent newspaper articles about the building's

future - are repeatedly being invoked. Though like Marx's spectre, they may

serve as a reference to the idea of social justice, which would be thwarted

by the luxury conversion of this long-term derelict building, the naming of

these names from a journalistic point of view is guaranteed to grab people's

attention. Which demons and spectres are conjured up or suppressed is always

notoriously a question of vested interests, the past a permanent invention of

the present.

Matthias Groebel likes to trace obscure tales and

handed-down stories in his paintings, videos and artist's books, for example

when he amalgamated photographs from the Golden Chamber of St. Ursula in

Cologne and the Musée Royal de l'Afrique Centrale in Tervuren, Belgium into

motifs from the dance of death in his exhibition Collective Memories from

2003; or for example in his video Raymond, where he associated freely

available audio material of a professor of child psychology and an interview

with Blackhawk, a colourful, larger-than-life New York figure from the new

media scene, to form a parable about conspiracy theory. Groebel is always

concerned with the question of how stories originate, how fiction and reality

co-mingle and which media and techniques of communication are utilized. In

the case of the Tower House it was a passing reference by a friend whilst out

walking through London that kindled his interest, the initial spark being

delivered in the oldest mode of tradition - oral narration. Groebel resourced

all further material for his artists book Safe from Demons on the net. He

processed all his knowledge about the building and its historical and

contemporary background through this filter, including any possible errors in

tradition and items of dubious veracity. Stories without a money-back

guarantee, so to speak.

.

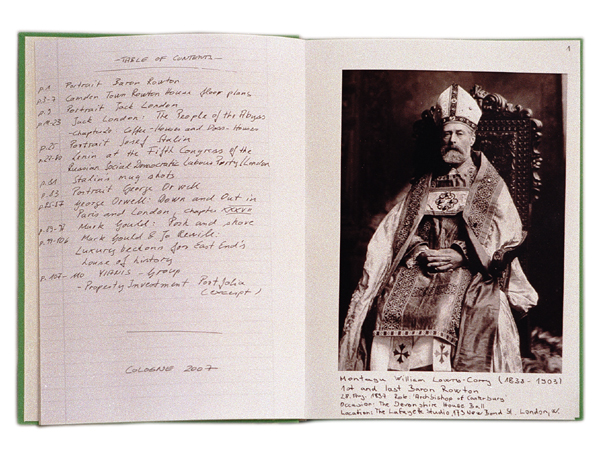

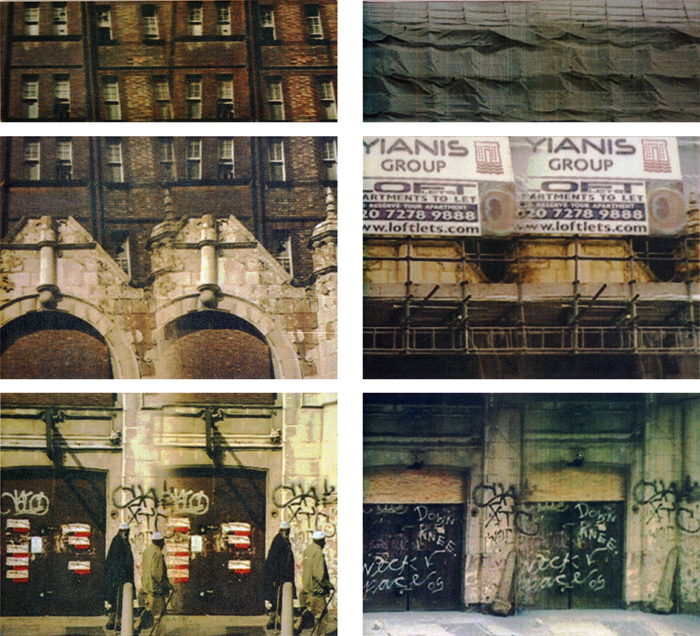

In his

book Matthias Groebel transfers only the more recent sources by hand, namely

two newspaper articles in The Guardian and The Observer about the planned conversion

of the house into flats. This seemingly medieval principle of reproducing

texts turns the supposed sequence of old and new media on its head, a

principle that fundamentally characterizes its artistic aim. Thus the

six-part group of pictures, upon which Tower House can be seen, is the

product of numerous medial translations. Captured by a stereo camera, Groebel

chose stills from all the recorded material, processed them on his computer

and transferred them by means of his painting apparatus which he devised

himself, onto the canvas by spraying many transparent layers of acrylic paint

upon one another by means of a computer-guided airbrush gun. The computer

replaces the hand of the artist just as similarly ideas of authenticity and

originality associated with it have long since been abandoned.

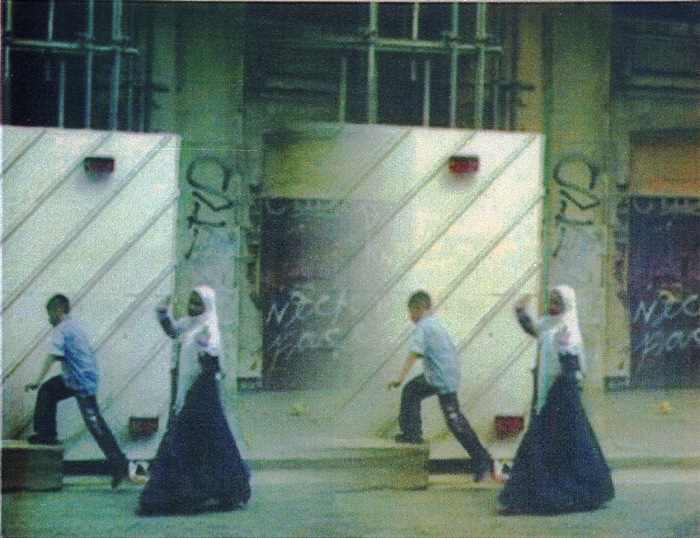

Of course, it isn't by any means a new

insight that the medium of painting - just like any other medium of pictorial

composition using technical aids - has always been mediated. The process of

distancing, which is associated with the manifestation of the apparatus, is

particularly accentuated in the more recent pictures by Matthias Groebel by

the use of the stereo camera. The stereo camera, which records two almost

identical images in parallel with minor deviations in perspective, does not

organize the pictorial space centrally, but from a number of perspectives. As

Bernd Stiegler commented on stereoscopy, one is "confronted by the

strangeness of another view of the way things are organised. The images do

not seem to be simulacra of reality, but rather backdrops and staffages of a

theatre with depth of field, but without any corporeality, as two-dimensional

figures arranged within the pictorial space".1 They become stages upon

which the individual protagonists, such as two passers by, are able to enact

their performance.

save from demons, 85 × 110 cm, acrylic on canvas,

2006

It

is worthy of mention, however, that a coherent image develops at first glance

- despite the double distancing of perception through the use of the stereo

camera and the painting machine, without which such a precise repetition of

the motif would hardly be possible. The almost identical doubling of the

pictorial elements is not immediately apparent, inasmuch as the artist does

not further emphasize the joins. We encounter a familiar pattern here from

the psychology of perception: in spite of all the knowledge about the degree

to which our eye is mediated and there being a permanent distance to reality,

we are nevertheless all too ready to believe the supposed coherence of the

compositions.

Matthias

Groebel introduces a further feature to Tower House, namely the element of

time. In this way about one and a half years have passed between the capture

of the images forming the group of pictures on the left and those on the

right. If the left column of pictures shows the desolate and already rundown

building, whose erstwhile function would have remained hidden without

additional information, the right group of pictures evinces further evidence

of decay, such as the bollard leaning in the corner of the entrance. However,

now the building is enclosed in scaffolding, the banner of the property

developer pointing to its future use. Different time levels and perspectives

are superimposed upon one another and it is already possible to discern the

demons of the future.

Astrid Wege

1

Bernd Stiegler, Theoriegeschichte der Photographie, (Munich, 2006) 67.

tower house, 230 × 210 cm, acrylic on canvas, 2005 -

06

Download as Adobe® PDF

back